This is a cross post with Innovations for Poverty Action's blog": Reposted with permission.

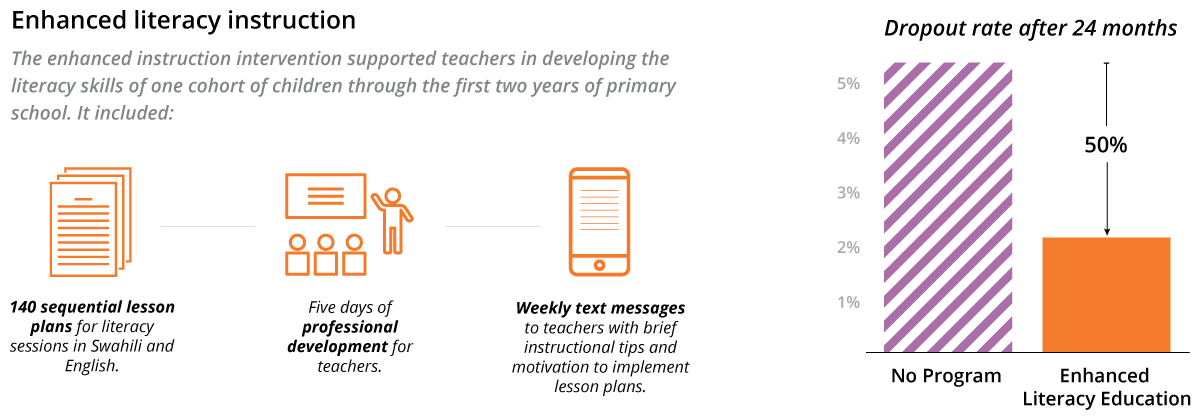

The Health and Literacy Intervention (HALI) project replaced expensive in-person coaching with text messages and found that they effectively supported teachers in improving their pedagogy, helped children learn to read, and reduced dropout by 50 percent (full study summary here, paper here).

For some, text messages are merely a tool for undermining children’s ability to spell. But could they also help children to read in parts of the world where this help is needed most? And in doing so, could text messages address one of the toughest challenges in education worldwide--literacy.

If you’d have asked me ten years ago what is required to improve global literacy, I would have focused at the level of the classroom. We were starting to discover from the gradual spread of Early Grade Reading Assessments (EGRA) that many children – probably most children – in poor countries were attending school for years and still not learning to read. We knew classrooms were over-crowded and poorly resourced and children had little experience of literature at home. So the challenge was: how can we give teachers the skills to surmount the odds and teach their class to read?

Ten years on and this problem is far from solved, but a recent systematic review finds that teacher training combined with a structured curriculum is one of only two types of education intervention that ‘works in most contexts’.

So now I would say that giving a teacher the skills they require to teach reading is no longer the biggest challenge. It’s how to give all teachers these skills. Everywhere. All the time. The focus has shifted from classroom to system.

One of the challenges of scale-up is that teachers – in common with all other kinds of human being – need a lot of support to change their behaviour. Typically in-person coaching is needed for teachers to learn new skills and apply them consistently, day after day for the months and years required for a child to learn to read. It can be a challenge for an education ministry to set up and maintain such an extensive system of quality support.

In the HALI project we wondered if a literacy improvement effort could succeed without expensive, intensive in-person coaches. Our project involved the elements of many others – teacher training workshops and scripted lesson plans - but we replaced coach visits to classrooms with a weekly text message. The text messages involved two-way communication: they aimed to prompt teachers to conduct key activities with the children, but also to find out how they were doing. As a result we were able to create a virtual community of practice, where questions, challenges and successes of one teacher could be shared with the others. Phones were used to send teachers a small amount of money ($0.50 a week or 1% of a beginner teacher salary) to help fund the communication. Although teachers received the money regardless of whether they responded, the response rate was high: 87% of messages received responses. Interestingly teachers were much more likely to respond when we asked them a question than when we simply sent them information. The two-way communication was critical in creating the virtual community. Teachers felt their opinions were valued and felt that the messages they received were tailored to their needs rather than indiscriminate spam.

The messages were successful. Teachers told us they felt more supported. There were also large changes in behaviour. Teachers were much more likely to do the things we know are critical for effective early literacy instruction – focusing on letters and sounds rather than on words and sentences, and helping children engage directly with text rather than just copying from the board. More important yet, the program also helped children to learn to read. By the end of two years children improved in reading letters, words and stories in comparison with a control group. They were also less likely to drop out of school. This study provides the first rigorous evidence that improved instruction can encourage children to stay in school. Our qualitative research tells us that children often make the decision to drop out of school themselves and the quality of the instruction they receive is a crucial factor.

.

So, are text messages the answer to providing quality education at scale? There are many reasons why they are only a partial answer at best. Our study found improvements in learning that were large when compared with many other types of intervention. But projects that use in-person coaching have typically found larger improvements. This suggests that coaches can’t be replaced by mobile phones, but coaching can certainly be supplemented by technology in order to reduce cost and to provide additional expertise for struggling coaches. Text messages also have the advantage that they can provide support in areas that people won’t or can’t reach. Coaches understandably end up providing more support to the schools in nearby urban centres that can be easily reached by public transport, and spend less time supporting schools at the top of mountains or at the end of long dirt roads that turn to mud for months at a time.

The technological revolution is already underway in teacher support. Tablets are being used to guide coaching and classroom instruction. Showing a teacher a video of exemplary teaching can be so much more effective than any verbal explanation. Our study showed that text message communication helped. In other contexts, social media or other technology may be the right platform to create a sense of community and sharing of information among teachers. In Bangladesh, teachers were successfully supported through conference calls, but in Kenya text messages did the job. In fact, the Kenyan government is using text messages and tablets as it attempts its ambitious national reading program (Tusome or ‘let’s read’) to reach over 20,000 schools.

In tackling the problem of providing quality education to every child across a region or nation we have yet to score many significant victories. But with careful studies that test the elements of an effective system, we may get there. And technology clearly has a role to play. Text messages are cheaper than people and they travel further and faster than people too. And yet, after the buzz or the beep that signals their arrival, they can have a powerful effect in supporting teachers and helping children to read.